Image copyright Leeds Trinity University

Image copyright Leeds Trinity University

Opinion: Embargoes help oil the machinery of newsgathering

Following on from Colin Kelly’s thoughts on news embargoes for RadioToday, journalist and lecturer Richard Horsman offers a different perspective.

Read Colin’s opinion piece here

Here’s the story: Simon Mayo, the very unhappy Radio 2 presenter who chose to leave the station after being forced to work in a format which didn’t work for him or his equally uncomfortable co-host, found a new gig in commercial radio. This is part of a trend. Chris Moyles, Eddie Mair, Chris Evans and now Simon have all handed in the pass at the Beeb to take up high profile roles in a newly-confident UK commercial radio sector.

Making the move is an art in itself. The objective is to get as much coverage as possible from other media normally too far up their own importance to acknowledge the massive audiences these and other radio giants draw every day.

Simon started teasing his move on social media, letting first Zoe Ball and then Chris Evans have their moments in the sun as their new shows started .. playfully announcing an announcement, driving fans and radio anoraks to distraction as he kept them waiting.

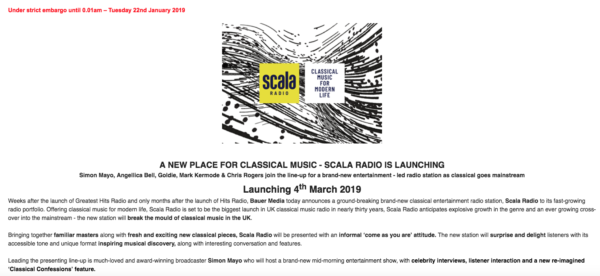

Meanwhile Bauer had their plans well advanced for Scala Radio. These things don’t happen overnight. Simon’s announcement was the icing on the cake, an announcement timed for Tuesday 22nd January. But across the country, newsdesks were told in advance with an embargoed press release.

The BBC’s Media Correspondent Amol Rajan broke that embargo, and tweeted the news a day early.

1/ More big news in UK radio: Bauer Media are launching a new classic/entertainment radio station: Scala Radio. And @simonmayo is their big name signing. He'll do a show 10am to 1pm 6 days a week. Will still do BBC Film show with Mark Kermode

— Amol Rajan (@amolrajan) January 21, 2019

And that, I believe, is a problem. Here’s why.

An embargoed story is … complicated. It has no legal basis. News releases often have big, bold enhanced large-font banners across the top screaming “Under strict embargo until 0.01am Tuesday 22nd January” or similar. You’d think the writs would fly and the rozzers turn up to cart off an errant journo to the cells if they ignored such a directive.

But in reality it’s no more than a gentlemen’s agreement between a source and a publication. The former gives information, and pictures, and interview opportunities in advance of a big announcement. The deal is that they get better quality coverage because journalists can do a better job. Instead of scrambling the story out one scrappy line at a time until a complete picture builds up, an embargo allows for a bit of craft, style and professionalism to be used. Photographs can be taken in a nice setting with relaxed subjects. Interviews can be scheduled, with reporters who’ve had time to read the background, not just the first paragraph of a news release.

One example that comes to mind is the announcement of a new Marie Curie hospice in Bradford. My newsroom knew of the announcement a week in advance. That gave us time to interview fundraisers, nursing staff, potential patients and their families; and to apply a delicacy of approach to the emotive topic of care for the dying. The local paper, meanwhile, was able to set a graphic designer to work creating a border of daffodils for the front page on embargo day. Marie Curie, of course, would benefit hugely from the additional emphasis given to what was all round a good news story for the city.

Trying to embargo bad news works less well. When Eric Pickles was leader of the model Thatcherite conservative administration in Bradford City Hall he brought in sweeping reforms; changes to the way public services were delivered that involved mass selloffs, redundancies and pain for a workforce taken very often unawares. As part of the process he started holding off the record briefings for trusted journalists on a Monday morning. “On Wednesday we’re selling the old folks’ homes. On Thursday we’re privatising school meals” or whatever. I forget the detail, but you get the drift.

Attending these briefings involved an understanding that we would not break the stories ahead of their public disclosure. They were embargoed.

This effectively tied our hands when – for the only time in my career – I really did receive a plain brown paper envelope with a leaked copy of the plans for residential care, delivered under the front door by what we’d now call a whistleblower; a concerned civil servant who risked their job to put details of the controversial proposals in front of a journalist. We stopped attending the Monday briefings after that. Others didn’t.

Breaking an embargo has no legal consequences, but can cause massive reputational damage. News works by means of contacts. Relationships with contacts give access to key players, those players give quotes that are vital to newsgathering. Contacts work by mutual trust.

Bust an embargo, and there’s a short term gain. Your outlet gets the credit for breaking the story first. Everyone else is running to catch up, and the ‘nice’ treatments go out of the window. Just publish what you’ve got, now.

The long term pain is that the organisation who gave the information under embargo will never, ever do so again. They’ll give it to all your competitors, and you’ll be the one, potentially the only one, to have missed it. The macho response to this is to say a decent journalist will find out by doing journalist-y things, and that any newsroom worth the name should know what’s going on without being ‘spoon fed’. Or at the very least will have a mate working for a rival who forwards the embargoed email on the QT to keep your backside out of the flames.

There’s some justice to this argument. But fundamentally, an embargo is one of the techniques that oils the machinery of newsgathering. It makes the process easier and less stressful for everyone involved … at least on a good news story, something light and fluffy, uncontroversial – like the move of a DJ to a brand new national radio station.

Did Amol Rajan demonstrate massive journalistic cajones by putting out the story a day early? No. I don’t know the details. I’m too far from the front line these days. But for anyone to bust an embargo for a bit of personal glory, if he did, doesn’t impress me much.

It doesn’t seem to have upset Bauer that much either, as they were happy to appear on Rajan’s Radio 4 Media Show after the event.

Maybe, just maybe they did so through gritted teeth, but the fact they went on at all allows a more cynical interpretation that possibly they colluded to break their own embargo, because of the profile and status Rajan enjoys. I don’t know. I can speculate all this without fear of legal consequences because an embargo has no legal status. “Journalist puts out story he knows about, even if that will piss off rivals” is the allegation, and that’s hardly defamatory.

I’d be sorry to see embargoes go. They’re a useful device in the right circumstances. I feel more sorry for the outlets that respected the Mayo release restriction, only to see Rajan bask in the glory of his ‘exclusive’. Maybe this is just part of the publicity game, hyped up and on steroids in the social media world. There’s always been the game of cat and mouse between hack and flack, and this is just the latest manifestation of it. But at a time when the news media is facing a crisis of trust, and allegations of manipulation and fakery at state level, the last thing we need to do is to make a new rod for our own backs.

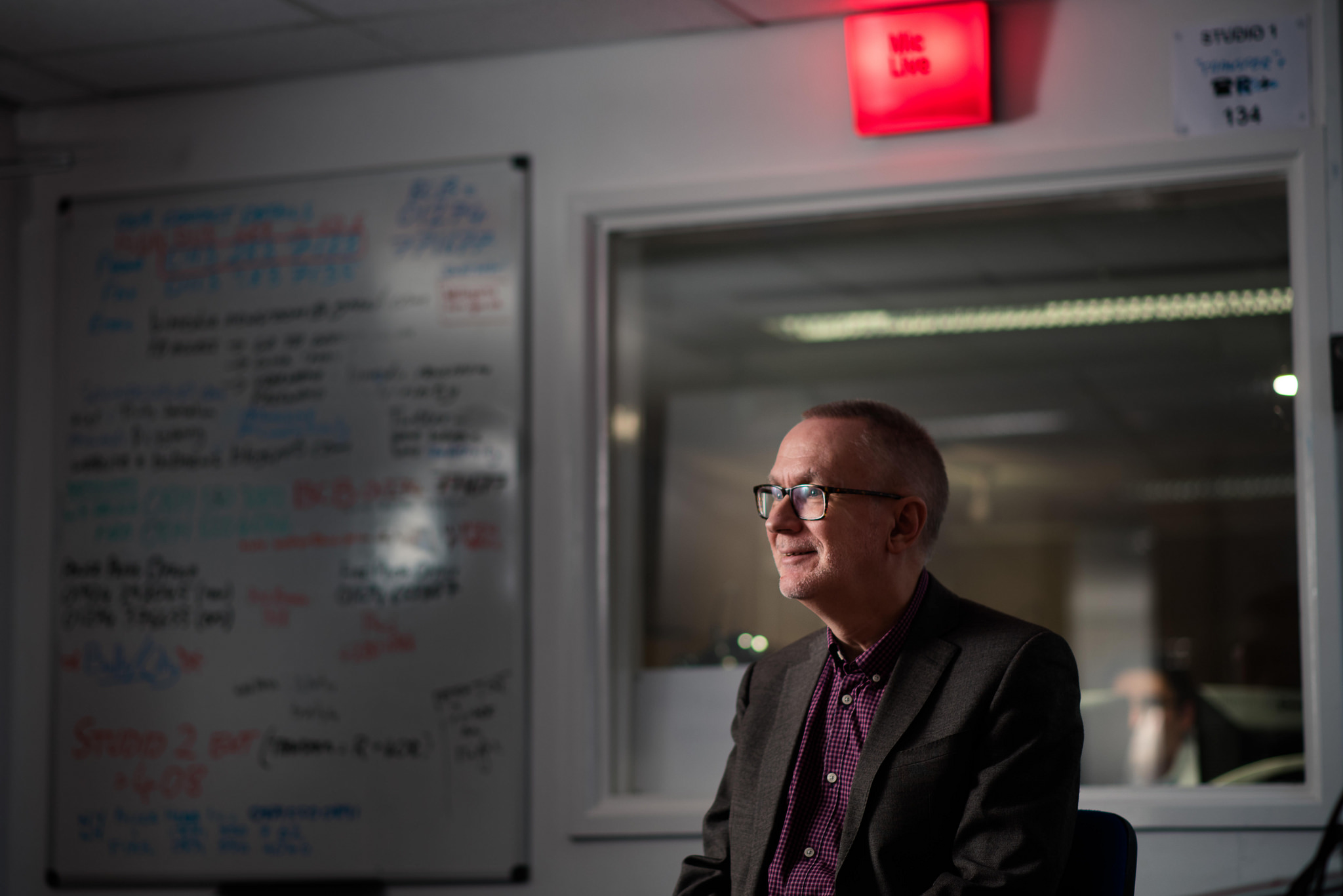

Richard Horsman is a former radio news editor and award-winning journalism trainer. Read more from him at rhorsman.blogspot.com

Posted on Thursday, January 24th, 2019 at 1:32 pm by Guest